Isaac Murdoch

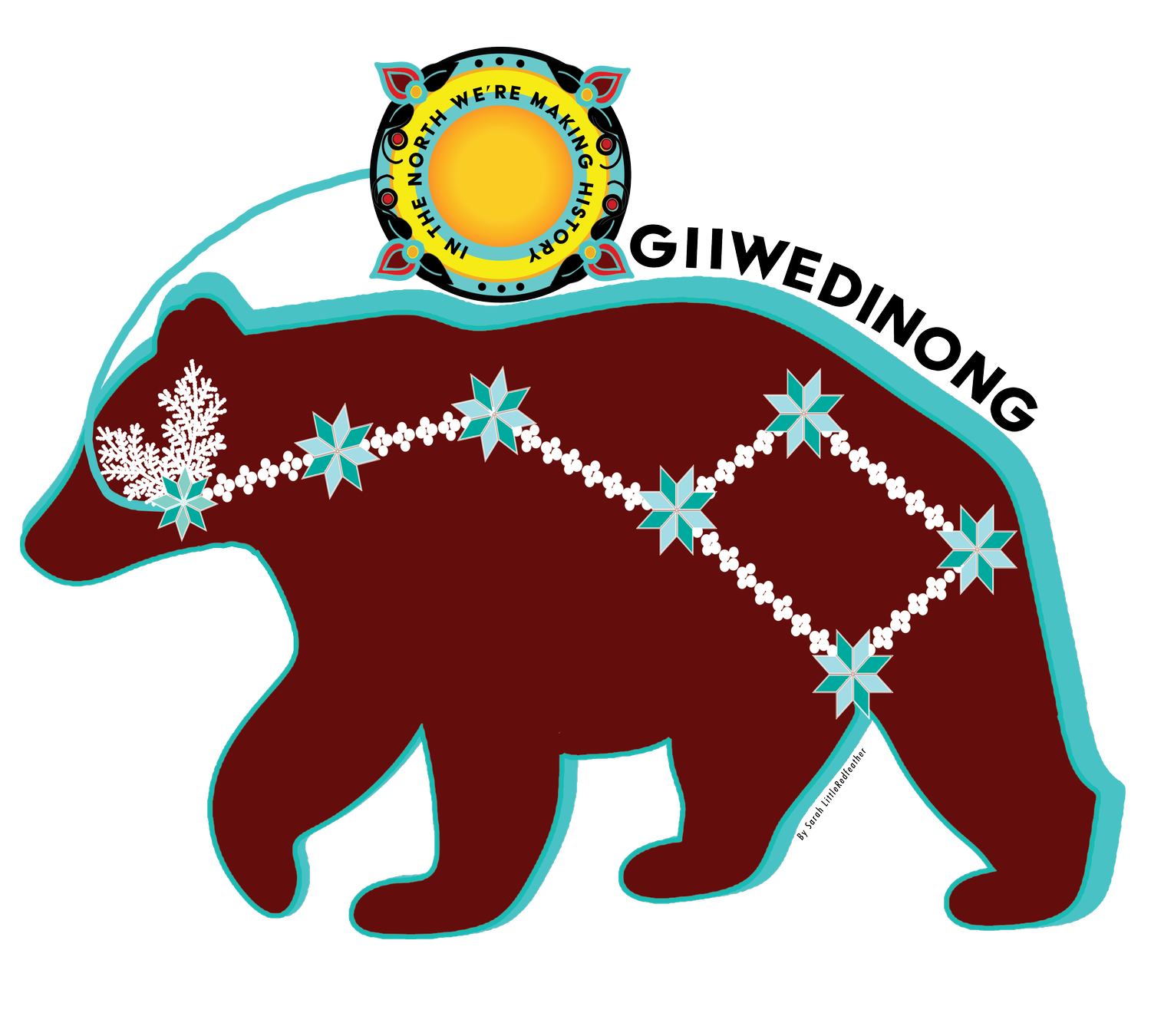

Isaac Murdoch's Thunderbird Woman, "Water is Sacred," artwork that is featured at Giiwedinong Museum as a mural on the building painted by Brian Dow, Red Lake Band of Ojibwe. This artwork is part of the revolution of Water Protectors.

Thunderbird Woman is "1/2 thunderbird, and 1/2 human. An environmental super hero." - Isaac Murdoch

Thunderbird Woman, "Water is Sacred."

“We’re in a sacred story”: The meaning of the #RejectTeck bird you’re seeing everywhere

For protection, look to the Thunderbird and honour the women

The design is a Thunderbird disguised as a regular bird to protect its eggs from the power in the ground.

I was removed from the land at the age of five, apprehended by Indian agents. But I remembered the stories about Thunderbirds trying to protect future generations. They have a special relationship with future generations, and there’s a balance between the Thunderbird and the Serpent, who is always trying to get the eggs of the Thunderbird.

For me, the Thunderbird is like a superhero. It can restore life and it can help protect us from the powers that weren’t meant to be brought up from the ground.

And that bird is a mom. It represents women, who protect life. Down at Standing Rock, they kept talking about the black snake and that’s when I made the Thunderbird woman. She’s another superhero, half-Thunderbird and half woman, who came down to fight the black snake.

Women have a higher rate of being murdered, displaced or missing than anyone else on this Earth when it comes to protecting the planet. My heart is with the people in South America and women all over the world sacrificing themselves for future generations all over the world. So, it’s also a commemoration.

We’re in a sacred story right now, together

A thousand years from now, people are going to be telling the sacred story of the battle between the Thunderbird and the Serpents. We’re in that story now and it’s a sacred story. My parents and my grandparents were warriors. I come from a long line of warriors. They fought colonialism and the U.S. government. They fought the British and they fought for their lands. When I came along, they always said this power we have cannot be killed by the bow and arrow, it’s in the hands of the Thunderbird. If we want to survive, we have to make our offerings. We have to start telling the story. That’s what they told me: not to physically fight but to make our offerings. So, I’ve always used art as peaceful action, but also as a way to create these symbols as medicine for whoever is using them. That’s how my mind is. And I’ve always felt that it’s highly important to let these birds do the work. So, when I see people carrying the reject Teck signs, I see that these birds are helpers. They just go all over the place. The imagery pulls people together. If I see someone with my images tattooed on them, I know that we are all on the same team. I think about people and their relationship with the land and waters. I think about the solidarity we have with land and trees. I also think about how art brings diversity together and how we are able to celebrate each other’s diversity.

I’m so blessed to be a part of this and to see humanity come together. Follow Isaac on Twitter at @IsaacMurdoch1

Biography

Isaac Murdoch, whose Ojibway name is Manzinapkinegego’anaabe/Bombgiizhik is from the fish clan and is from Serpent River First Nation. Murdoch grew up in the traditional setting of hunting, fishing and trapping. Many of these years were spent learning from Elders in the northern regions of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Isaac is well respected as a storyteller and traditional knowledge holder. For many years he has led various workshops and cultural camps that focuses on the transfer of knowledge to youth. Other areas of expertise include: traditional Ojibway paint, imagery/symbolism, harvesting, medicine walks, & ceremonial knowledge, cultural camps, Anishinaabe oral history, birch bark canoe making, birch bark scrolls, Youth & Elders workshops, etc.

He has committed his life to the preservation of Anishinaabe cultural practices and has spent years learning directly from Elders.